Over the past year I made my way through much of the 13 seasons of Room to Improve , an Irish TV series featuring architect Dermot Bannon. He tackles a home revamp project in each episode and his clients are often challenging. (It’s on Amazon Freevee , and If you decide to watch, I recommend starting around season 5.)

As I watched, I was reminded once again how home building is a lot like making a website. Web designers and architects use processes that tend to parallel each other: Discovery, Design, and Development for web designers; Discovery, Design, and Construction for architects. It wasn’t a new observation; I’ve often used that analogy. But here I’m sharing five lessons worth thinking about for web designers, learned from Room to Improve.

Lesson #1: Involve UX staff from beginning to end

The lead architect or the UX designer should play a role in all the steps from discovery through development. In my work as a UX designer, I’m often asked to come into projects midstream and produce specific deliverables like site maps and wireframes. Even with the best briefing, without the benefit of actually being part of discovery, that work will never be as well-informed or inspired.

Once those deliverables are completed, I may not be involved further in the project. That would be akin to Bannon handing off blueprints to the contractor and not being involved further. But that’s not what happens on his TV show. Rather, he visits the construction site all along the way to ensure everything is on track.

Similarly, the UX designer should not only follow a website project through development, but also perform UAT (user acceptance testing) after development is complete. That ensures the project successfully meets its goals.

Lesson #2: Solve budget problems before they happen

One amusing thing about Dermot Bannon’s Room to Improve is that his projects almost always get into budget trouble (“boo-jit” that is, with Irish brogue). For anyone who has built a website — or a house — budget problems seem to be more the rule than the exception. For most projects, Bannon works with his estimator to ensure there is a substantial contingency budget for the inevitable times when unexpected issues arise (which they always do). The client is made aware of the contingency budget up front and if they make unplanned requests along the way, they are cautioned that the cost will come from the contingency, reducing what’s remaining for unforeseen problems that may occur. This kind of budget transparency is so much better for the client and the architect (or web designer) than the alternative: nickel and diming the client for every extra request they make or every unforeseen construction problem that comes along. It’s so much better to under promise and over deliver than vice versa (see my article on that topic). In the rare event that contingency isn’t used, the project is delivered under budget. What a delight that is for the client!

Lesson #3: Present site maps & wireframes together

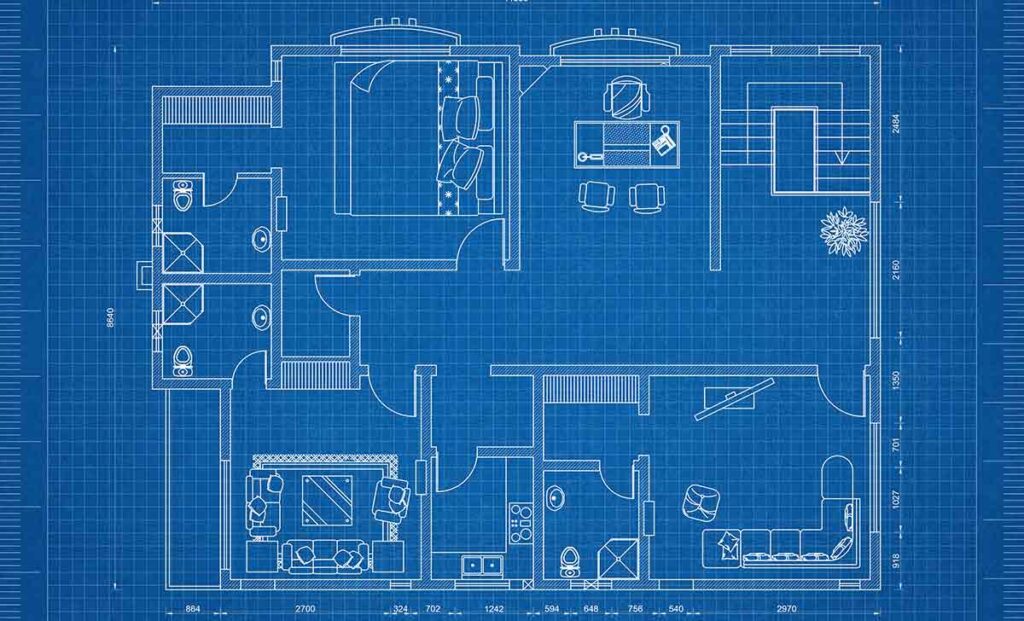

In his TV series, Bannon is really good at presenting design options to his clients. Before he reveals his designs, he recaps what he learned during the discovery phase and reminds the client about the goals of the project. Then, he presents his work in a way that demonstrates how the goals are met by his designs. When presenting his ideas, he never shows only the floor plans — he always presents floor plans along with a 3D architectural model. This helps the client interpret the design: it makes the somewhat abstract floor plans more comprehensible.

For the same reasons, I believe the best approach for web design is to present site maps and wireframes simultaneously (unlike the typical approach of getting site map approval before beginning wireframes). This makes the site maps much more relatable and prevents misinterpretation of site maps by clients. (See my article about wireframes on that topic.)

Lesson #4: thoroughly review plans with the builder

In Bannon’s show, when a project is passed from the architect to the builder, sometimes there is confusion on the builder’s part of how to exactly interpret the blueprints. This creates mistakes and budget problems. Drawings and plans are only as good as the imperfect humans who make them and who read them. Plans (blueprints or wireframes) should not be allowed to speak for themselves. When plans are passed from the architect to the contractor (or from UX designer to developer) they should be discussed in detail. Then, as the building project proceeds, the UX designer and developer should be in touch continuously to be sure everything is on track (Lesson #1).

Lesson #5: Fight (tactfully) for what you know is right

Designers can learn a lot from Bannon’s tact with his clients. By no means is he a “yes man.” He has regular disagreements with clients. Those disagreements often result in being at loggerheads, stuck between his ideas and those of his clients. Yet, he seems to come out on top nearly always. How does he do it? He’s clear that he is the expert, having the training, knowledge and experience to know what to do. Because of that, he’s confident about his recommendations. He might say something like this to his clients, “Well ultimately it’s your decision of course, but I’m very confident that, if you take my recommendation, you will thank me for it when the project is finished.” Even though he sometimes sounds a bit smug, he is respectful of his clients and they usually agree in hindsight that he was right. At the end of each episode, when their homes are completed, it’s very common to hear clients comment that despite their disagreements, Dermot was right, and they are very happy they listened to him.

Isn’t that a great place to be for any professional service provider?